In Iceland, a tapestry of patterns, shapes and textures

Leonardo da Vinci was fascinated by water. The artist, an astute observer of the natural world, bestowed upon water a place of hierarchical importance, calling it “the vehicle of nature,” and wrote extensively about the liquid’s many forms and properties.

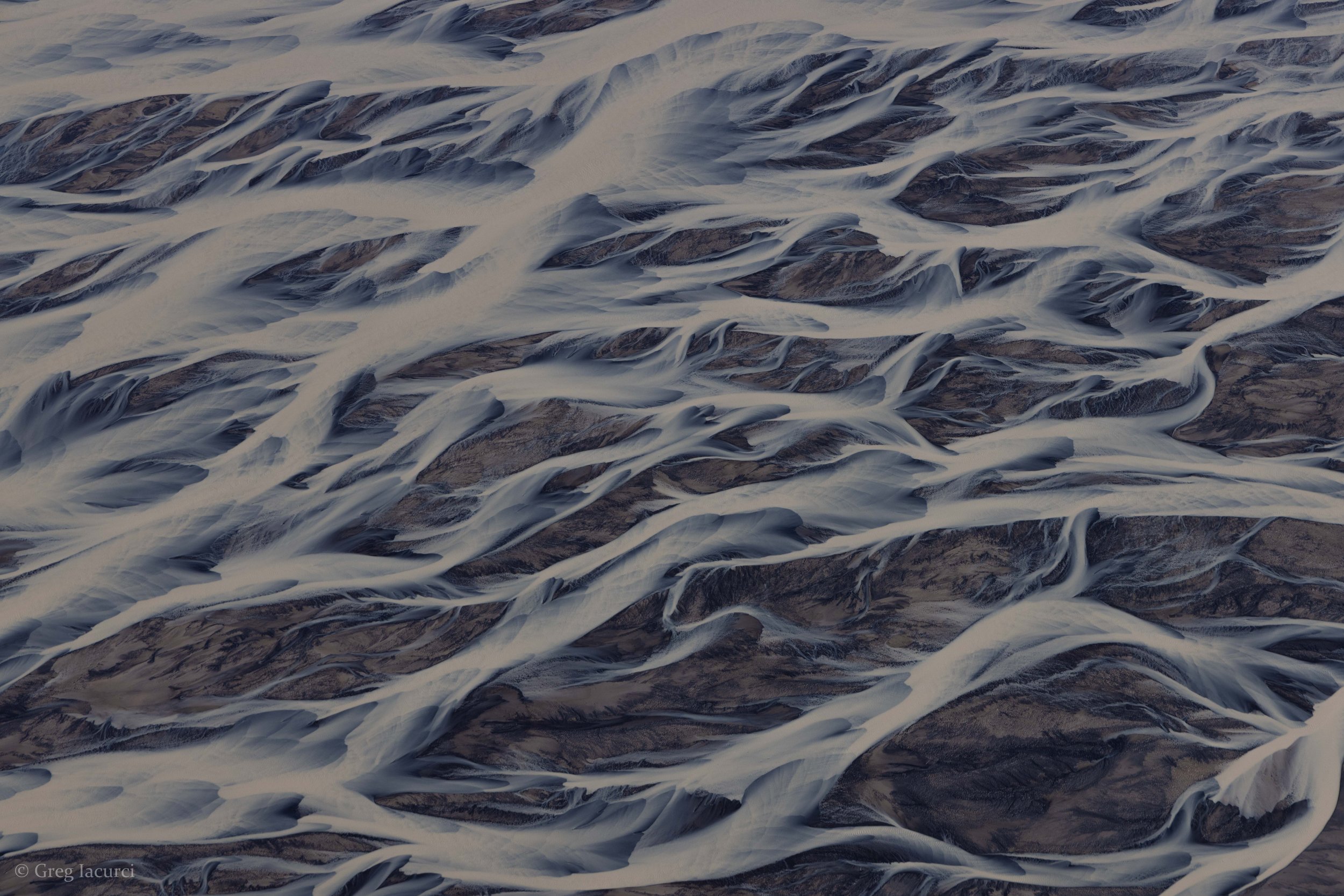

He described rivers as “veins of the earth,” which burst open from the summits of mountains and returned to the sea below. In Iceland, this vast circulatory network is inscribed on the land with unflinching clarity — but only from the right vantage point. Otherwise, it’s a gift hidden in plain sight.

In this case, I was flying 800 feet above the sands of the Skeiðarársandur, in the country’s southeast. From that perch, I saw sheets of meltwater cascading from the snaking tongues of Europe’s largest icecap, Vatnajökull, and branching in swirling ribbons across the broad and ancient glacial outwash plain.

From the air, Iceland’s south coast rivers offer an abstraction of patterns and colors. The ingredients: Glacial meltwater, silt and minerals.

Thousands of tributaries and rivulets — from slender, almost indiscernible curves to hulking watery tendrils — weaved in and out of each other with graceful chaos. The colors of the milky, sediment-rich waters bled into the grainy hues of black and tan as the torrent pushed inexorably toward the sea, which welcomed the river’s flow with an inviting glint of sunshine.

The tableau presented as something almost fake or unnatural, a vista so beautiful and otherworldly it must have emanated from Da Vinci’s masterful brushstrokes.

But, then again, that’s just Iceland for you — landscapes so freaking cool they seem like the stuff of dreams.

The famed Laugavegur trail winds 54 kilometers through the Icelandic highlands, from Landmannalaugar to Þórsmörk. Pictured here are various points along the route. The latter two mountains are respectively named Stóra-Grænafjall and Rjupnafell.

That trip in August was my third to the country, which continues to surprise in ways that leave me yearning to return.

As its nickname suggests, the Land of Fire and Ice is one of extremes. Among the most volcanically active countries in the world, Iceland is scorched and barren. In some areas, swaths of ash and fields of dried lava extend to the horizon, at times yielding to soaring black mountains and long-extinct craters.

But that starkness is also juxtaposed by countless waterfalls licking the hillsides, blankets of spongy, green moss, icebergs resting elegantly in frosty glacial lagoons, and the pastoral serenity of farms dotted with grazing sheep and horses.

From top to bottom: Goðafoss; Jökulsárlón Glacier Lagoon; Skógafoss; and Kvernufoss.

This time around, my eye was especially drawn to the country’s abounding patterns, shapes and textures: moss clinging to otherwise desolate inclines and plains in delicate swirls and drips; peaks that stand like impossibly perfect cones and pyramids; ash from past volcanic eruptions etched onto glaciers’ weathered surfaces in streaks and circles.

Vestrahorn, a mountain that hovers over the black sand beach Stokksnes, often exudes a dark, foreboding air at sunset. But at sunrise, its crumbling rocks ignite to reveal a different personality, its black and brown overtones mixed with subtle shades of yellow, orange and green. Even familiar places can hold new secrets unveiled with repeat visits.

Vestrahorn mountain sits above the black sand beach Stokksnes at sunset (top) and sunrise (bottom).

Wisps and plumes of geothermal steam seeped from cracks in the earth on the famed Laugavegur trail, a 54-kilometer trek through the Icelandic highlands from Landmannalaugar to Þórsmörk. The hot, white smoke buffeted colorful rhyolite mountains, a rainbow tapestry of blues, oranges, yellows, greens, pinks and reds.

Elsewhere, the path traversed fields of obsidian, smooth volcanic glass that twinkled like black diamonds in the sunlight, and cut through ominous deserts where black-green monoliths sprung like mirages from parched flats.

The Laugavegur trail meanders through an impressive diversity of wild landscapes, from colorful rhyolite mountains shrouded in geothermal steam to ash-laden deserts of black-green pyramids juxtaposed by glaciers. The bottom photo is of Mount Einhyrningur, which translates to “The Unicorn.”

Iceland’s braided rivers are so visually captivating they offer something akin to natural hypnosis. The waterways are a byproduct of glacial melt, imbued with fabulous colors by silt and mineral deposits as the ice sheets grind the underlying bedrock to a pulp. Iceland’s glaciers also lie atop active volcanos; while the climate heats and melts the ice sheets from above, geothermal processes also do so from below. Heated water dissolves more minerals, and therefore acquires more color.

I took two photo flights over the south coast rivers — one near the capital, Reykjavik, in the southwest, and the other near Skaftafell in the southeast — and was mesmerized by the natural Rorschach test on display. In a single photo frame, an observer might see blue flames, a snake’s open mouth, a chicken’s foot or perhaps the links of a chain — or at least, that’s what my mind conjures. The combination of meandering water and sand creates limitless possibilities.

Rivers and abstract patterns along Iceland’s south coast.

And yet, Iceland’s braided rivers may be relegated to memory within just a few generations. Glaciers, which feed the waterways, cover about 10% of Iceland’s surface. But climate change is causing them to melt at an unsustainable rate. In 2019, Iceland held a funeral for one recently extinct ice sheet, the former Ok glacier (pronounced “awk”); it had been over 3 kilometers long as recently as 2000.

All but the country’s biggest glaciers are poised to disappear within a century. Within two, Iceland will likely be ice-free, choking off the vast and vibrant circulatory system envisioned by Da Vinci. Just as veins are an essential biological life force, the loss of Iceland’s ice — and the magical river systems it creates — would be akin to losing a vital part of the country’s soul.